The more breast cancer treatments a radiologist administers, the more reimbursements he or she typically receives. This is known, in healthcare, as fee-for-service medicine — and lots of experts don’t like it, largely because it creates an incentive to provide as much care as possible, regardless of whether patients get any healthier.

“When we see patients who have breast cancer, their first concern is if it yields the same cure rate, which it does, and the second is whether it’s more toxic, and it’s not,” says Justin Bekelman, a radiation oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania whose practice focuses on treating prostate cancer. “Then it’s like, wow, if that’s true and the new breast cancer treatment is only three weeks, its a no-brainer.”

It seemed like a no-brainer to radiation oncologists too. In 2011, their trade group, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, found that the two options were “equally effective for in-breast tumor control and comparable in long-term side effects” for a huge percent of patients.

doctors don’t have incentives to stay up-to-date on new treatments

This makes it all the more surprising that, three years later, new research published today in the Journal of the American Medical Association shows that the vast majority of radiation oncologists aren’t using the new treatment.

The slow adoption of a faster and cheaper technology — one that delivers a better patient experience at a lower cost — isn’t just an issue with breast cancer treatments. It speaks to a lot of what’s screwed up in the larger American health care system. Doctors don’t have big incentives to stay up-to-date with new treatments. Sometimes, it’s actually financially ruinous for them to do so.

“This is the case where everyone could win, except for the radiation oncologists, who would be getting less money for fewer treatments,” says Zeke Emanuel, a bioethicist at University of Pennsylvania and co-author of the new study with Bekelman, the oncologist. “We have a persistence of no-value care, and that’s not good.”

Two-thirds of early-stage breast cancer patients get the wrong treatment

The new research looks at the insurance records of thousands of women treated for early-stage breast cancer between 2008 and 2013. It uses the billing claims that their providers submitted to see what type of treatment they got.

“We have a persistence of low-value care.”

It finds that use of the new treatment — known as hypofractionation whole breast irradiation — definitely increased from 2008 through 2013, as more research came out proving its efficacy. In 2008, when there was nearly as much research as there is today, 10.6 percent of women for whom the new treatment was endorsed ended up receiving it.

By 2013, that number had grown to 34.5 percent. That’s way more than 2008 — but also nowhere near a majority of patients getting a newer, faster, and equally good treatment as the older option. While the United States has made progress since 2008, for Emanuel, that one-third figure still raises the question: why, two years after national guidelines endorsed the new treatment, were most breast cancer patients not getting it?

Why don’t doctors pick the better treatment?

One cynical answer has to do with money: the more treatments a radiologist administers, the more reimbursements he or she typically receives. This is known, in healthcare, as fee-for-service medicine — and lots of experts don’t like it, largely because it creates an incentive to provide as much care as possible, regardless of whether patients get any healthier.

The billing records that Bekelman, Emanuel, and their co-authors examined show that insurance plans were billed more than $4,000 more for patients who received the older, longer course of treatment than those who had the newer, shorter chemotherapy sessions. Patients also had slightly higher (about $100) out-of-pocket costs for radiation-related expenses.

“In terms of the financial pressures, right now we work in an environment that rewards higher intensity care and quantity rather than quality,” says Bekelman. “It’s not the whole story, but it’s part of it. Our health-care system certainly doesn’t incentivize and may even disincentivize high-value cancer care.”

And there’s also the role of old habits being hard to kill, and radiologists relying on the same treatment they’ve used for years now. Yes, it is a bit more expensive and inconvenient for patients, but there’s no evidence that it’s actively harming their health.

“If you don’t take into account convenience, costs to patients, and costs to society, you can tell yourself that it’s not the worse option,” says Emanuel.

This could be true not just on the part of oncologists but on the part of patients, too, who might assume that the longer, more expensive course of treatment has to be better. In most other things we shop for, like cars and vacations, bigger and more expensive generally means higher quality. Why wouldn’t health care be like that too?

“In cancer care, we’ve always thought that more is better,” Bekelman says. “The fact is more isn’t always better. Sometimes less is just right. But making that change in mindset can be difficult.”

Low-value care happens everywhere in the health care system

The financial incentives, the doctor preference, and patient attitudes — all of these add up to American women getting worse breast cancer care than women in other countries. In Canada, for example, more than 70 percent of eligible patients receive the new treatment. That’s double the rate here in the United States.

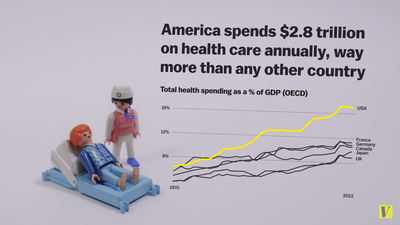

This isn’t an issue limited to breast cancer care. The American health care system is replete with examples of doctors providing care that doesn’t help people get better — care that wastes time, money, and energy on the part of patients and providers. Medicare, for example, spends an estimated $1.9 billion on care that study after study shows doesn’t make people healthier.

And by rewarding volume over value, the American health are system makes this type of unnecessary, unhelpful breast cancer treatments especially easy to provide. The incentives are all there to encourage doctors to provide more care, even if, like the older breast cancer treatment methods, it isn’t the best choice for the patient.

(Article Excerpt and Image from How we treat breast cancer exposes a huge systematic issue in American health care, December 10, 2014, www.news.yahoo.com).